Pipelines is a powerful concept that is language independent and is “a must” for any developer to master.

This post discusses concept of pipelines and how it can affect application speed; it also assumes some Go and basics of concurrency knowledge.

A naive prime calculation algorithm is chosen deliberately for the sake of demonstration in this post and, instead of improving the algorithm, speed-up is achieved by utilizing process composition (using concurrency and parallelism).

Pipelines

I like to think of Pipelines as an umbrella term that involves data processing with number of transformations and branching.

From aesthetic point of view, my favorite, is a functional style pipeline, IE in ruby:

is_prime = ->(k) do

return false if k < 2

is_divisible = ->(n) { (k % n).zero? }

((k/2).downto(2))

.to_enum

.none?(&is_divisible)

end

consume = ->(k) { puts k }

0.upto(1000) # generator

.lazy #

.select(&is_prime) # filter stage

.each(&consume) # consume stage

But aesthetics alone isn’t not enough: Go provides something Ruby doesn’t at the moment, and that’s what makes Go great.

Why pipelines are great

- gives high level overview what a system does

- composable: allows swapping/injecting new “stages” relatively simply.

In reality, building a pipeline isn’t trivial:

- handling errors isn’t always obvious: ignore or stop the whole process?

Adding concurrency takes it to the next level of complexity:

- distributing expensive computation accross available computational units

- stages coordination

- efficient resource usage: start/stop processing as soon as needed, pooling

Go pipelines

Equivalent to the above Ruby example is this Go snippet:

package main

func isPrime(n int) bool {

if n < 2 {

return false

}

for i := 2; i <= n/2; i += 1 {

if n%i == 0 {

return false

}

}

return true

}

func main() {

consume := func(i int) { println(i) }

for i := 0; i <= 1000; i += 1 {

if !isPrime(i) {

continue

}

consume(i)

}

}

Keeping the logic “high level”, allows retaining readability similar to the functional style one. Yes, it’s single process but we’ll fix it later

Process Composition

Let’s call the above example SingleProcess and describe it with pseudo diagram:

(Note: {...} denote a running process)

{generator |> isPrime |> consume}

The above pipeline runs as a single process and is a sequence of corresponding “stages”.

Go has first-class support for multiprocess computations. Go’s processes are very lightweight and are called goroutines and allow computation composition in various ways;

for example below pseudo diagram (see func ProcessPerStage below) denotes composition of generator, isPrime, consume stages running as three separate processes(goroutines).

{generator} |> {isPrime} |> {consume}

Even though it’s utilizing multiple processes the way they’re composed is very much equal to the single process: the pipeline handles only single value at a time.

More complex example(Nworkers) with an n number of isPrime processes(aka “workers”)

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

...

{generator(N)} >| {isPrime} >|> {consume}

|> {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

Note: each number generated by the generator is picked up by one of the isPrime “workers”(unlike “pub-sub” composition where a value is published to all of the subscribers)

This pipeline handles n values at a time.

Even more complex example:Parallel with a P parallel Nworkers pipelines.

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

...

{generator(0..N/2)} >| {isPrime} >|> {consume}

| {isPrime} >|

|> {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

|> {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

...

{generator(N/2..N)} >| {isPrime} >|> {consume}

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

| {isPrime} >|

P=2 in the example above and each generator generates half of the numbers to be processed by corresponding pipeline.

This pipeline handles P*n values at a time.

Measuring performance improvements

Back to our original goal of improving performance.

We need to get a baseline to see if we are getting any improvements. Benchmarks are part of Go’s standard library and that’s what we’re going to use for measurements. Our benchmark will look like this:

func run(b *testing.B, fn primePipeline, n int) {

var (

m sync.Mutex

sum int

consume = func(p int) { m.Lock(); sum += 1; m.Unlock() }

)

for i := 0; i < b.N; i += 1 {

fn(0, n, consume)

}

}

func BenchmarkSingle_x10(b *testing.B) { run(b, SingleProcess, 10000) }

func BenchmarkProcessPerStage_x10(b *testing.B) { run(b, ProcessPerStage, 10000) }

func BenchmarkNWorkers2_x10(b *testing.B) { run(b, Nworkers(2), 10000) }

func BenchmarkNWorkers5_x10(b *testing.B) { run(b, Nworkers(5), 10000) }

func BenchmarkNWorkers100_x10(b *testing.B) { run(b, Nworkers(100), 10000) }

func BenchmarkParallel_2_Nworkers10_x1(b *testing.B) { run(b, Parallel(2, Nworkers(10)), 1000) }

func BenchmarkParallel_5_Nworkers10_x10(b *testing.B) { run(b, Parallel(5, Nworkers(10)), 10000) }

func BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers10_x100(b *testing.B) { run(b, Parallel(10, Nworkers(10)), 100000) }

// etc

Where:

- first 2 benchmarks use

SingleProcess, andProcessPerStagecompositions correspondingly. Nworkershelper constructs the “N workers” composition withN=2,5,100workers runningisPrimeParallelhelper constructs the “P parallel N Workers” composition whereP=2,5,10andN=10

Benchmark doesn’t really need the results therefore consume just sums the primes together.

Compositions

Take a look what I ended up measuring:

SingleProcessProcessPerStageNworkersParallel

They all do same thing differently.

package main

import (

"sync"

)

type primePipeline func(int, int, func(int))

func isPrime(n int) bool {

if n < 2 {

return false

}

for i := 2; i <= n/2; i += 1 {

if n%i == 0 {

return false

}

}

return true

}

func SingleProcess(a, b int, consume func(int)) {

for i := a; i <= b; i += 1 {

if !isPrime(i) {

continue

}

consume(i)

}

}

func ProcessPerStage(a, b int, consume func(int)) {

var (

numbers, primes = make(chan int), make(chan int)

done = make(chan struct{})

)

go func() {

defer close(numbers)

for i := a; i <= b; i += 1 {

numbers <- i

}

}()

go func() {

defer close(primes)

for i := range numbers {

if !isPrime(i) {

continue

}

primes <- i

}

}()

go func() {

for i := range primes {

consume(i)

}

close(done)

}()

<-done

}

func Nworkers(nWorkers int) primePipeline {

return func(a, b int, consume func(i int)) {

var (

numbers, primes = make(chan int), make(chan int)

wg sync.WaitGroup

)

go func() {

defer close(numbers)

for i := a; i <= b; i += 1 {

numbers <- i

}

}()

wg.Add(nWorkers)

go func() {

for j := 0; j < nWorkers; j += 1 {

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

for n := range numbers {

if !isPrime(n) {

continue

}

primes <- n

}

}()

}

}()

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(primes)

}()

for i := range primes {

consume(i) // map

}

}

}

func Parallel(p int, nWorkers primePipeline) primePipeline {

return func(a, b int, consume func(int)) {

var (

wg sync.WaitGroup

r int = (b - a) / p

)

wg.Add(p)

for i := 0; i < p; i += 1 {

go func(k int) {

nWorkers(k*r, (k+1)*r, consume)

wg.Done()

}(i)

}

wg.Wait()

}

}

Running Measurements

$ GOGC=off go test -bench .

PASS

BenchmarkSingle_x1-8 5000 356184 ns/op

BenchmarkSingle_x10-8 50 25900177 ns/op

BenchmarkSingle_x100-8 1 2003477330 ns/op

BenchmarkProcessPerStage_x1-8 2000 629103 ns/op

BenchmarkProcessPerStage_x10-8 50 28780083 ns/op

BenchmarkProcessPerStage_x100-8 1 2084416804 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers2_x1-8 2000 605472 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers2_x10-8 100 17286883 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers2_x100-8 1 1047627418 ns/op

...

ok 95.666s

See the appendix for the full list of benchmarks.

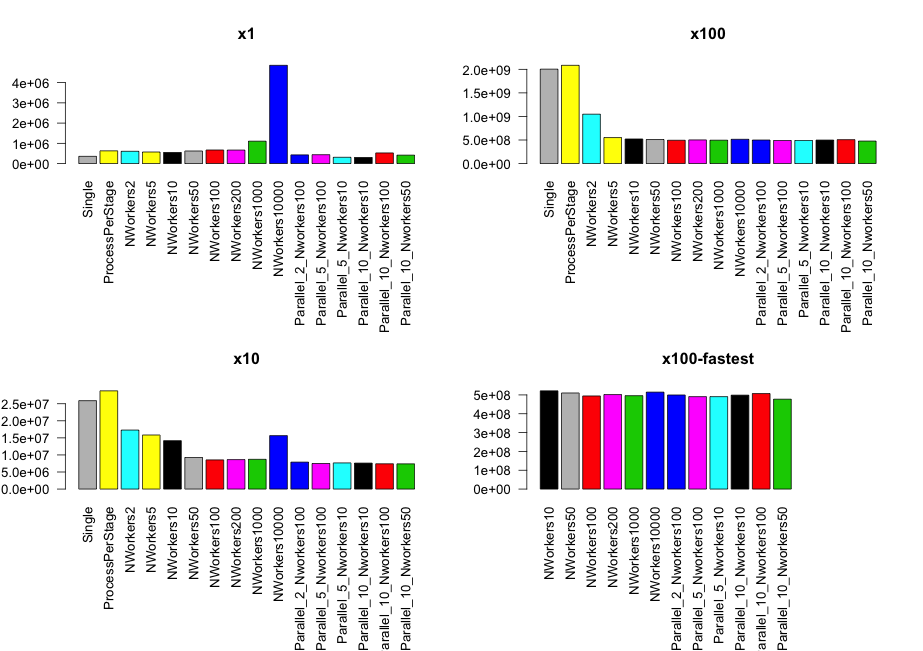

Visualising results

Takeaways

Small x1 data set: 1000 numbers

Single Processis as fast as concurrent alternativesNworkers10000is the slowest due to the overhead of starting all the goroutinesParallel_5_Nworkers10turns out to be the fastest: best composition

Medium x10 data set: 10000 numbers

- All concurrent approaches beat the

SingleandProcessPerStagecompositions Nworkers10000is still the slowest among the fastest due to the overhead of starting all the goroutines

Largest x100 data set: 100000 numbers

- All concurrent approaches beat the

SingleandProcessPerStagecompositions Nworkers10000is finally as fast as the restParallel_10_Nworkers50composition is the winner in on this data set- Surprisingly all the compositions perform equally well: which probably needs an investigation why it’s the case.

Conclusions

- Distributing work onto available computational units can lead to increased performance

- There are many ways to distribute the work across the units through various process-compositions

- Performance depends on the size of the data set and the composition

- Experiment, measure and pick the best one

- Go provides poverful means to create simple and complex compositions

Links

Appendix

Transforming Benchmark data into CSV

cat /tmp/bench.txt | gsed \

-e 's/^Benchmark//' \

-e 's/\s\+/,/g' \

-e 's/-8//g' \

-e '1d' -e '$d' \

-e 's/_\(x10*\),/,\1,/' \

-e '1,1s/^/name,cat,num,time,metr\n/' \

> /tmp/bench.csv

Where:

/tmp/bench.txt- contains the output of the benchmarkgsed- GNU sed. (brew installgnu-sedon OSX)/tmp/bench.csv- resulting csv file

Visualising results with R

data = read.csv("/tmp/bench.csv", header = T)

x1 = data[data$cat == "x1",]

x10 = data[data$cat == "x10",]

x100 = data[data$cat == "x100",]

xf100 = data[data$name != "Single" & data$name != "ProcessPerStage" & data$name != "NWorkers5" & data$name != "NWorkers2",][data$cat== "x100",]

plot.new()

par(mfcol=c(2,2))

barplot(x1$time, names.arg = x1$name, las=2, col=x1$name, main="x1")

barplot(x10$time, names.arg = x10$name, las=2, col=x10$name, main="x10")

barplot(x100$time, names.arg = x100$name, las=2, col=x100$name, main = "x100")

barplot(xf100$time, names.arg = xf100$name, las=2, col=xf100$name, main = "x100-fastest")

Running Measurements

$ GOGC=off go test -bench .

PASS

BenchmarkSingle_x1-8 5000 356184 ns/op

BenchmarkSingle_x10-8 50 25900177 ns/op

BenchmarkSingle_x100-8 1 2003477330 ns/op

BenchmarkProcessPerStage_x1-8 2000 629103 ns/op

BenchmarkProcessPerStage_x10-8 50 28780083 ns/op

BenchmarkProcessPerStage_x100-8 1 2084416804 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers2_x1-8 2000 605472 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers2_x10-8 100 17286883 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers2_x100-8 1 1047627418 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers5_x1-8 2000 571273 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers5_x10-8 100 15843289 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers5_x100-8 2 551634068 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers10_x1-8 2000 550591 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers10_x10-8 100 14172803 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers10_x100-8 2 521673833 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers50_x1-8 2000 621635 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers50_x10-8 200 9255698 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers50_x100-8 2 510328577 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers100_x1-8 2000 670851 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers100_x10-8 200 8545942 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers100_x100-8 3 494487285 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers200_x1-8 2000 667479 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers200_x10-8 200 8632608 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers200_x100-8 3 501877974 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers1000_x1-8 2000 1105869 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers1000_x10-8 200 8710296 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers1000_x100-8 3 495943705 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers10000_x1-8 500 4854573 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers10000_x10-8 100 15651293 ns/op

BenchmarkNWorkers10000_x100-8 2 514827970 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_2_Nworkers100_x1-8 3000 429188 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_2_Nworkers100_x10-8 200 7894608 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_2_Nworkers100_x100-8 3 499677761 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_5_Nworkers100_x1-8 3000 438370 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_5_Nworkers100_x10-8 200 7486469 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_5_Nworkers100_x100-8 3 490868915 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_5_Nworkers10_x1-8 5000 310080 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_5_Nworkers10_x10-8 200 7663384 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_5_Nworkers10_x100-8 3 490913444 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers10_x1-8 5000 305239 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers10_x10-8 200 7607736 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers10_x100-8 3 498725339 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers100_x1-8 3000 525166 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers100_x10-8 200 7405168 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers100_x100-8 2 507191373 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers50_x1-8 3000 416034 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers50_x10-8 200 7386612 ns/op

BenchmarkParallel_10_Nworkers50_x100-8 3 477299967 ns/op

ok 95.666s

Test machine:

Model Identifier: MacBookPro11,3

Processor Name: Intel Core i7

Processor Speed: 2.6 GHz

Number of Processors: 1

Total Number of Cores: 4

L2 Cache (per Core): 256 KB

L3 Cache: 6 MB

Memory: 16 GB

bench.csv

name,cat,num,time,metr

Single,x1,5000,356184,ns/op

Single,x10,50,25900177,ns/op

Single,x100,1,2003477330,ns/op

ProcessPerStage,x1,2000,629103,ns/op

ProcessPerStage,x10,50,28780083,ns/op

ProcessPerStage,x100,1,2084416804,ns/op

NWorkers2,x1,2000,605472,ns/op

NWorkers2,x10,100,17286883,ns/op

NWorkers2,x100,1,1047627418,ns/op

NWorkers5,x1,2000,571273,ns/op

NWorkers5,x10,100,15843289,ns/op

NWorkers5,x100,2,551634068,ns/op

NWorkers10,x1,2000,550591,ns/op

NWorkers10,x10,100,14172803,ns/op

NWorkers10,x100,2,521673833,ns/op

NWorkers50,x1,2000,621635,ns/op

NWorkers50,x10,200,9255698,ns/op

NWorkers50,x100,2,510328577,ns/op

NWorkers100,x1,2000,670851,ns/op

NWorkers100,x10,200,8545942,ns/op

NWorkers100,x100,3,494487285,ns/op

NWorkers200,x1,2000,667479,ns/op

NWorkers200,x10,200,8632608,ns/op

NWorkers200,x100,3,501877974,ns/op

NWorkers1000,x1,2000,1105869,ns/op

NWorkers1000,x10,200,8710296,ns/op

NWorkers1000,x100,3,495943705,ns/op

NWorkers10000,x1,500,4854573,ns/op

NWorkers10000,x10,100,15651293,ns/op

NWorkers10000,x100,2,514827970,ns/op

Parallel_2_Nworkers100,x1,3000,429188,ns/op

Parallel_2_Nworkers100,x10,200,7894608,ns/op

Parallel_2_Nworkers100,x100,3,499677761,ns/op

Parallel_5_Nworkers100,x1,3000,438370,ns/op

Parallel_5_Nworkers100,x10,200,7486469,ns/op

Parallel_5_Nworkers100,x100,3,490868915,ns/op

Parallel_5_Nworkers10,x1,5000,310080,ns/op

Parallel_5_Nworkers10,x10,200,7663384,ns/op

Parallel_5_Nworkers10,x100,3,490913444,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers10,x1,5000,305239,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers10,x10,200,7607736,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers10,x100,3,498725339,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers100,x1,3000,525166,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers100,x10,200,7405168,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers100,x100,2,507191373,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers50,x1,3000,416034,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers50,x10,200,7386612,ns/op

Parallel_10_Nworkers50,x100,3,477299967,ns/op

Thank you!